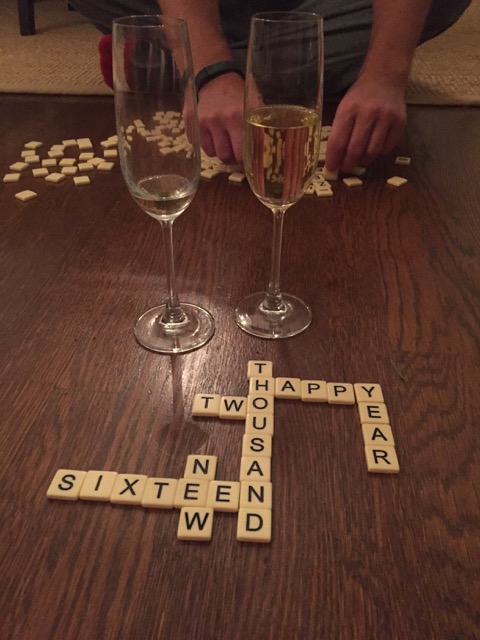

RAISE A GLASS, WE'RE CELEBRATING THAT I'M SOBER

By Lisa S.

Today I have been sober for one year. 365 days.

Sober.

While I am extremely proud that I have not had one single drop of alcohol for the past year, using the word “sober” still makes me feel uncomfortable. I am, after all, sober. But sober — the word itself conjures up a bad taste in my mouth: the deep, dark nasty feelings of shame and guilt associated with being an alcoholic.

But, I am, after all, an alcoholic. Aren’t I?

Not the drunk-at-noon, can’t-keep-a-job (although my parents might argue with me here!), I-need-my-next-drink-NOW sort of alcoholic. But maybe the more dangerous type. The one drink turns quickly into three turns quickly into one bottle turns quickly into I can’t remember… and regret and anger and I’m too old for this shit, again and again and again. Waking up morning after morning with regret after regret — telling myself this wouldn’t happen again, and of course, living through the shame, depression and frustration at myself when it did.

And how many of us can relate to this type of alcoholic? The type that’s too easy to shrug off as a bad night (or hell, a good night even) because all my friends are doing it, or it’s not really binge drinking, or you’re only young once, or I’ve had a long week, or it’s the holidays.

“Sometimes not drinking does strange things to friendships. ”

After finally getting up the resolve to DO something about my problem (much easier to use an innocuous word like “problem”), I challenged myself to one year without alcohol. Anything less than a year, I figured, and I’d find a way to cheat or not hold myself to it. Anything more, I figured, was admitting to something much more than I was willing, while I was sipping red wine on a cross-country flight last January, not ever really believing I’d make it a year.

But I did.

I stayed out of bars, and I stayed in my room, alone. I beat myself up a lot, and judged myself, and in the beginning, judged others. And then, after a lot of work and patience and digging and hurting and searching, I slowly stopped. I’ll admit, it took awhile.

Sometimes not drinking does strange things to friendships. To friends who do drink and don’t want to tempt you, or don’t know what else to invite you to do if they’re going out, or who figure you’re judging them if they’re drinking.

So, eventually, I went into a (few) bars. I left my room. I sat with friends as they had a glass of wine, or two or five. And I realized, I didn’t care what they did. It just mattered what I did. Or rather, what I didn’t do.

“I’ve looked at the deepest, ugliest parts of myself and realized I was OK with what I saw in those dark corners.”

And in the end, sitting here, drinking what seems like endless cups of coffee and sparkling water in this dry fucking year, I realize I’ve done a lot. I’ve travelled the world, bared my soul to people I hardly know (that’s what I’m doing, you realize, every time you ask why I’m not drinking and I honestly tell you), made new friends and made huge life changes. I’ve looked at the deepest, ugliest parts of myself and realized I was OK with what I saw in those dark corners because I know I can accept or change anything.

All without alcohol.

So, please, raise your glass of champagne (please have champagne or a gin and tonic for me — it’s been so long, and bubbles or Hendricks would really hit the spot right now) and join me in toasting my incredible year without alcohol.

Today not only marks the anniversary of the last time I drank, but also marks the first day of the rest of my life, where each day I make the conscious decision whether or not to imbibe.

So, cheers.

(And make mine a sparkling water, for now.)

Lisa S. leads a full-time existence: working in communications, being a slave to her FitBit and enjoying time with her family, friends and dog. After a few glasses of wine post sober year achievement, she’s back on the wagon and living without alcohol.